The twenty-fourth book I read in 2018 was Jane Austen Cover to Cover: 200 Years of Classic Covers by Margaret C. Sullivan. This is a lovely little coffee table book with full-color images of the covers of various editions of Austen's novels over the years, from first editions through movie tie-ins to mash-ups. Some are lovely; some are laughable; and a great multitude are anachronistic, particularly when it comes to fashion and the current standard of beauty.

Some gleanings:

The famed Peacock Edition of Pride and Prejudice was published in 1894 and was so iconic that, despite peacocks not being mentioned in the text, many later covers revert to the theme.

Northanger Abbey wins the category of most inappropriate cover art, with many illustrators and marketers taking at face value the Gothic trappings Austen was parodying. (Sample cover blurb from the 1965 Paperback Library edition: "The terror of Northanger Abbey had no name, no shape -- yet it menaced Catherine Morland in the dead of night!")

There is an e-book which manages to misspell both the title (Sense and Sensibility) and the author's name on the cover.

Oldcastle Books published a faux-pulp edition of Pride & Prejudice, featuring a Colin Firth portrait with a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth and the cover blurb "Lock Up Your Daughters... Darcy's In Town!"

This book definitely stirred up my never-very-dormant collector's vibe. One disappointment, however, is that Sullivan often discusses the interior illustrations of a particular edition but provides no images. I suspect that the rights might have been expensive and/or unavailable, but I'd frankly rather she didn't bring them up than talk about them and leave me hanging.

Saturday, June 30, 2018

Thursday, June 28, 2018

Book review: Empire by Steven Saylor

The twenty-third book I read in 2018 was Empire: The Novel of Imperial Rome by Steven Saylor. The sequel to his Roma, it picks up with the Pinarius family where the previous book left off, in the reign of Augustus.

Despite being a thicker book than its predecessor, Empire covers only 127 years, whereas Roma encompassed a millennium. This is, in large part, due to the much wider historical basis for the early years of the empire versus the comparative lack of documentation for the founding, kings, and early republic. It also necessarily narrows the focus on the Pinarius family to four generations. In theory, this ought to allow for more characterization, but the Pinarii are a literary conceit: they exist as witnesses to history rather than as active participants.

Unfortunately, Saylor's perfunctory treatment of female characters persists, including one who turns out to be more literally a Woman in a Refrigerator than one would believe possible so many centuries before household appliances. More common are women who simply drop out of the narrative, never to be mentioned again, or die off-screen. A characteristic examples is the final Pinarius wife of the book, Apollodora, who is introduced as the object of the protagonist's desire, serves the matrimonial purpose of allying the fictional protagonist with a historical personage, gives birth to a son and heir (but no other children, despite the couple's sex life being presented as vigorous), pops into the plot again when her (historical) father is put to death, and then ... nothing. Her last appearance in the book is to silently nod to a comment her husband makes and then go off to bed, unallowed by the author even to express an anodyne opinion on the events of the day.

Empire suffers from the defect, common in quasi-educational fiction, of having one character explain to another events with which he should already be familiar for the benefit of the reader ("As you know, Marcus...."). There also seem to be more small errors in this book than in its predecessor: missing prepositions, "tale" in place of "tail," etc.

My other complaint is that Saylor is perhaps too trusting of contemporary historical accounts; if Suetonius or Plutarch or someone said that this or that out-of-favor late emperor performed a particular feat of debauchery, by golly, it must be so (not to mention the novelist's benefit that it makes for racy purple prose). In Roma, Saylor demytholigized the legend of Hercules and Cacus; it's disappointing that here he reports on Apollonius of Tyana at breathless face value.

Monday, June 25, 2018

Church camp 2018

Wednesday, June 6, 2018

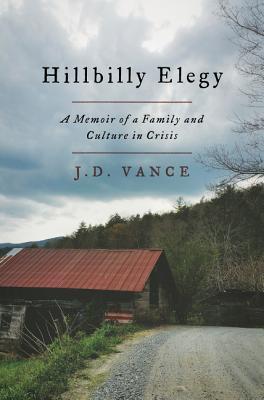

Book review: Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance

The twenty-second book I read in 2018 was Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J. D. Vance. The book caused a big stir when it was published in 2016, and it's been on my radar for a while; but I only now got around to reading it.

Vance tells the story of his own dysfunctional family, which is not at all unusual in the memoir genre, but he also claims, as indicated by the subtitle, that, contra Anna Karenina, that his family was unhappy not in its own way but in a way that indicts the culture in which he grew up: in his case, diaspora Appalachians.

While media attention around the book has focused on Vance's "up by the bootstraps" ending, the vast majority of this book deals with the dysfunction which he has (so far) escaped. The meat of the story begins with his Mamaw and Papaw leaving Kentucky for a shot at a better life in Ohio. His grandparents' marriage was intensely dysfunctional itself during their childrearing years, but by the time J. D. came along, they had reconciled into the only safe haven he would know as a boy. His mother, herself traumatized by the violence of her childhood home, descended into addiction, serial monogamy, and worse, leaving J. D. and his older sister to depend on their grandparents and each other.

The first thing I must say about this book is that the language is vile. To the author, it may be unremarkable: he emphasizes that his family, especially his beloved Mamaw, was unusually vulgar, and he went from there into the Marines, where one expects that the language is hardly suitable for children. As a professional, however, Vance might realize that such language is inappropriate in some instances -- I doubt he uses it with a new client -- and in my opinion, the book is harmed by his choice to use it, not only in direct quotation but in his own narrative voice. While his story is moving and his analysis thought-provoking, the incessant obscenity prevents me from recommending the book to people I otherwise might. (See The Martian, which eventually got a bowdlerized classroom edition.)

The book aspires (I think) to be heart-warming and life-affirming, but some aspects of it leave me troubled rather than reassured about J. D. His affection for his grandparents is understandable but seems to lead him to condone actions that seem to me reprehensible. "Mamaw did it, and everything worked out," is not equivalent to "Mamaw acted wisely and in the best interests of the children involved." Many of the situations described in the book could just as easily have ended in tragedy as triumph and, in other families, have. In addition, I find his descriptions of the networking and connections that reaped him great rewards once he got to Yale Law to be revolting, verifying that it's not what you are capable of but who you know that weighs more heavily on the scales of success: once you are accepted into Yale Law (and learn which utensils to use in which order at a fancy restaurant), the rest of your professional life is set, which is nice unless you're not fortunate enough to be accepted into Yale Law.

Vance tells the story of his own dysfunctional family, which is not at all unusual in the memoir genre, but he also claims, as indicated by the subtitle, that, contra Anna Karenina, that his family was unhappy not in its own way but in a way that indicts the culture in which he grew up: in his case, diaspora Appalachians.

While media attention around the book has focused on Vance's "up by the bootstraps" ending, the vast majority of this book deals with the dysfunction which he has (so far) escaped. The meat of the story begins with his Mamaw and Papaw leaving Kentucky for a shot at a better life in Ohio. His grandparents' marriage was intensely dysfunctional itself during their childrearing years, but by the time J. D. came along, they had reconciled into the only safe haven he would know as a boy. His mother, herself traumatized by the violence of her childhood home, descended into addiction, serial monogamy, and worse, leaving J. D. and his older sister to depend on their grandparents and each other.

The first thing I must say about this book is that the language is vile. To the author, it may be unremarkable: he emphasizes that his family, especially his beloved Mamaw, was unusually vulgar, and he went from there into the Marines, where one expects that the language is hardly suitable for children. As a professional, however, Vance might realize that such language is inappropriate in some instances -- I doubt he uses it with a new client -- and in my opinion, the book is harmed by his choice to use it, not only in direct quotation but in his own narrative voice. While his story is moving and his analysis thought-provoking, the incessant obscenity prevents me from recommending the book to people I otherwise might. (See The Martian, which eventually got a bowdlerized classroom edition.)

The book aspires (I think) to be heart-warming and life-affirming, but some aspects of it leave me troubled rather than reassured about J. D. His affection for his grandparents is understandable but seems to lead him to condone actions that seem to me reprehensible. "Mamaw did it, and everything worked out," is not equivalent to "Mamaw acted wisely and in the best interests of the children involved." Many of the situations described in the book could just as easily have ended in tragedy as triumph and, in other families, have. In addition, I find his descriptions of the networking and connections that reaped him great rewards once he got to Yale Law to be revolting, verifying that it's not what you are capable of but who you know that weighs more heavily on the scales of success: once you are accepted into Yale Law (and learn which utensils to use in which order at a fancy restaurant), the rest of your professional life is set, which is nice unless you're not fortunate enough to be accepted into Yale Law.

Monday, June 4, 2018

Book review: It's All a Game by Tristan Donovan

The twenty-first book I read in 2018 was It's All a Game: The History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan by Tristan Donovan. The subtitle is misleading, as the overview actually starts well before Monopoly with games of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. From there it travels through chess and backgammon before jumping ahead to the game of Life (which admittedly has a longer pedigree than I'd assumed), Monopoly, Risk, Clue, Scrabble, Mouse Trap, Twister, the Ungame, Trivial Pursuit, Pandemic, and (as advertised) Settlers of Catan, with a pair of digressions on the use of board games to help POWs escape during WWII and the rise of AIs in chess and go.

There are a lot of interesting facts on parade here, including what exactly a "rook" is, how many games got their start in Canada before crossing the southern border, and exactly how convoluted the origin story of Monopoly is. The book could have used another editing run: Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Dave Arneson is consistently referred to as Dave Arenson, and the culprit in Clue is dubbed a "gentile" rather than genteel British murderer. Still, this was an interesting read. I learned some things and made a mental note of a few games I might pick up for our family to enjoy.

There are a lot of interesting facts on parade here, including what exactly a "rook" is, how many games got their start in Canada before crossing the southern border, and exactly how convoluted the origin story of Monopoly is. The book could have used another editing run: Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Dave Arneson is consistently referred to as Dave Arenson, and the culprit in Clue is dubbed a "gentile" rather than genteel British murderer. Still, this was an interesting read. I learned some things and made a mental note of a few games I might pick up for our family to enjoy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Blog Archive

Labels

- Agatha Christie (3)

- Alexander McCall Smith (23)

- apologia pro sua vita (49)

- Art Linkletter (29)

- Austeniana (10)

- bibliography (248)

- birthday (21)

- Charles Lenox (3)

- Christmas (29)

- deep thoughts by Jack Handy (16)

- Grantchester Mysteries (4)

- Halloween (10)

- high horse (55)

- Holly Homemaker (19)

- Hornblower (3)

- Inspector Alan Grant (6)

- Isabel Dalhousie (8)

- life-changing magic! (5)

- Lord Peter Wimsey (6)

- Maisie Dobbs (9)

- Mark Forsyth (2)

- Mother-Daughter Book Club (9)

- No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency (14)

- photo opportunity (103)

- pop goes the culture (73)

- rampant silliness (17)

- refrigerator door (11)

- Rosemary Sutcliff (9)

- something borrowed (73)

- the grandeur that was (11)

- where the time goes (70)