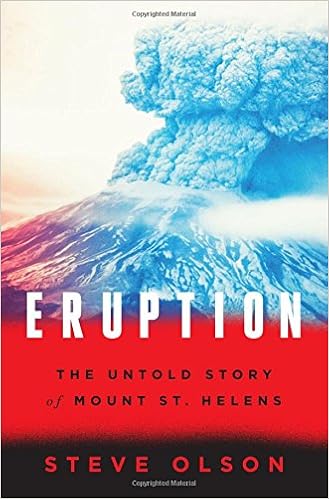

The eighteenth book I read in 2016 was Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount Saint Helens by Steve Olson. The eruption of Mount Saint Helens was a formative event in my childhood. I remember the news stories, the old man who wouldn't leave the mountain, the live Christmas tree we bought in 1980 with a thin coating of ash on the needles. And I've always been a sucker for real-disaster stories. I used to read the plane crash or earthquake feature stories in Reader's Digest, where a group of disparate people started their morning having no clue what was in store for them that day, and try to guess which ones would survive: "This paragraph says she thought about going to the grocery store while driving to the airport, so she must survive because otherwise no one would know what she had been thinking." So that made me a natural reader for this book about the eruption.

When it comes right down to 'who lives and who dies' the morning of the eruption, the mountain was remarkably fickle. Some people camping very close to the mountain survive, thanks to an intervening hill which provided some shelter from the pyroclastic flow; others farther away but with a clear view to the volcano die almost instantly. Some campers manage to hike out of the transformed landscape; returning after the eruption, they find that their friends were killed when a log fell on their tent, but the dogs with them somehow survived unscathed. Two men are riding horses; one takes shelter in a cave and dies; the other dives into a river as the explosion passes overhead, hikes several miles toward a nearby town ... and then dies anyway, unable to find help.

Irony abounds in the story of a conservation group lobbying to save old-growth forest from logging. A few days before the eruption, they lead a hike through a certain section of untouched forest, hoping to persuade the government to declare it a preserve, off-limits to loggers, so that future generations can see its virgin beauty. In seconds, the eruption flattens each and every one of those ancient trees far more completely than any logging company. (The conservation group switches to support preserving the destroyed forest as a historical site after the eruption so that the power of the volcano can be seen and appreciated.)

If you're interested in Mount Saint Helens or natural disasters in general, this is an enjoyable read, but the author reaches a bit, in my opinion, to find an axe to grind and a handful of villains to point to. The governor of Washington state at the time comes off very poorly in his telling, and she may well deserve to.

Olson's attempt to paint the CEO of the Weyerhaeuser logging company as a bad guy is less successful. Much is made of the company's refusal to stop operations in the area before the eruption, but as even the author admits, the wholly-inadequate designated "safe zones" were drawn up by government officials, not the company. In addition, one has to remember that no one knew when, or if, the volcano would actually erupt. It had been threatening for two months. If the company had idled its workers for that long, wouldn't it have been the target of complaints for an abundance of caution, depriving families in an economically-depressed area of income, particularly if the eruption had, as it could well have, turned out to be less dramatic than it did?

In any case, the Sunday morning eruption spared the lives of many men who would have died if the volcano had blown during a working day, a fact for which we can be thankful. George Weyerhaeuser did not speak to the book's author about the disaster, but despite Olson's best efforts to paint Capitalism Red in Tooth and Claw, he comes across as a decent guy: his company gave the father of a man considered dead but whose body was never found two years off with pay to try to locate his son's remains.

The reality of the situation is that, despite humanity's best efforts, natural disasters happen. It's hard to say what anyone in authority "should have" done to make things better, without a timetable of exactly when it was going to happen, how bad it would be, and which areas would be affected, things no one could possibly know. It's worth pointing out that one of the first people to die was a scientist at an observation station directly in the path of the explosion: if "more science" were the answer, one would think that the scientists wouldn't have put their own in harm's way. There are no fingers to point here.

Sunday, June 19, 2016

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2016

(73)

-

▼

June

(17)

- Book review: Lieutenant Hornblower by C. S. Forester

- Book review: The Titanic's Last Hero by Moody Adams

- Book review: Design for Murder by Carolyn G. Hart

- Book review: Mr. Midshipman Hornblower by C. S. Fo...

- Book review: Birds of a Feather by Jacqueline Wins...

- Book review: The Comforts of a Muddy Saturday by A...

- Book review: Maisie Dobbs by Jacqueline Winspear

- Book review: The Careful Use of Compliments by Ale...

- Book review: Texts from Jane Eyre by Mallory Ortberg

- Book review: Imperium by Robert Harris

- Book review: The Collapse of Parenting by Leonard Sax

- Book review: Eruption by Steve Olson

- Book review: A Charlie Brown Religion by Stephen J...

- Book review: Sidney Chambers and the Problem of Ev...

- Book review: Mystery of the Roman Ransom by Henry ...

- Book review: Spark Joy by Marie Kondo

- Birthday boy

-

▼

June

(17)

Labels

- Agatha Christie (3)

- Alexander McCall Smith (23)

- apologia pro sua vita (49)

- Art Linkletter (29)

- Austeniana (10)

- bibliography (248)

- birthday (21)

- Charles Lenox (3)

- Christmas (29)

- deep thoughts by Jack Handy (16)

- Grantchester Mysteries (4)

- Halloween (10)

- high horse (55)

- Holly Homemaker (19)

- Hornblower (3)

- Inspector Alan Grant (6)

- Isabel Dalhousie (8)

- life-changing magic! (5)

- Lord Peter Wimsey (6)

- Maisie Dobbs (9)

- Mark Forsyth (2)

- Mother-Daughter Book Club (9)

- No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency (14)

- photo opportunity (103)

- pop goes the culture (73)

- rampant silliness (17)

- refrigerator door (11)

- Rosemary Sutcliff (9)

- something borrowed (73)

- the grandeur that was (11)

- where the time goes (70)

No comments:

Post a Comment